Paradigm Shifts

Before we can fix the problem, we need to know what the problem isMitigation of metabolic risk should be a primary directive of all product formulation and engineering.

We don’t need a consumer referendum to deliver healthy foods—we need their forgiveness for failing to do so. Tomorrow’s foods will have metabolic health hard-wired at the level of the seed, the field, the factory, and the kitchen. To achieve this, innovation and the full power of the 4th Industrial Revolution must be unleashed to rapidly reimagine, reinvent, and reengineer a food system that delivers positive metabolic health outcomes for all. The proof will be in the pudding, and we must be held to account with metrics:

- are we increasing the number of metabolically healthy people?

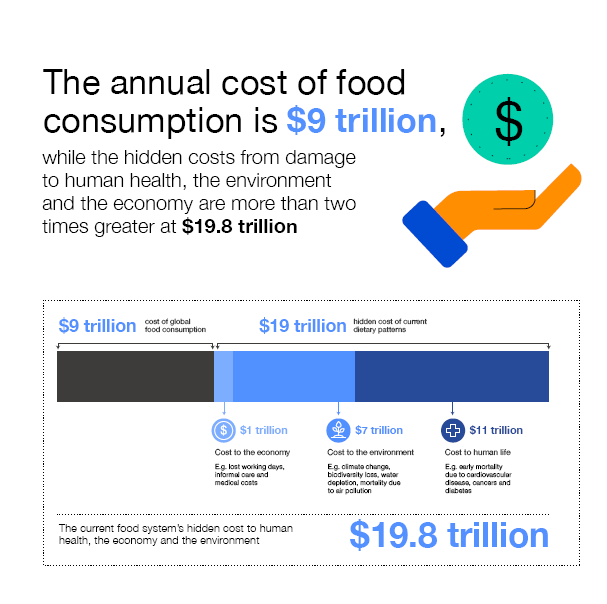

- how much have we reduced the *$11 trillion of harm to health that the food system causes?

* Source: The True Cost and True Price of Food, Scientific Group of the UN Food Systems Summit, June 2021

The hidden costs of food are rising by $1,000,000 every two seconds.

Source: Food System Economics Commission

Counter captured 22-JAN-2024 Click here for the most recent number.

…diet interventions that seek to alter the ‘external’ setting, or choice environment, tend to be more effective than those that target our ‘internal’ motivations.”

Reference:

Cadario, R., & Chandon, P. (2018). Which Healthy Eating Nudges Work Best? A Meta-Analysis of Field

Experiments. Marketing Science.

Ölander, F., & Thøgersen, J. (2014). Informing versus nudging in environmental policy. Journal of Consumer Policy, 37(3),

341-356.

An analysis to determine the current cost of externalities in the food system and the potential impact of a shift in diets to more healthy and sustainable production and consumption patterns reveals that the current externalities were estimated to be almost double (19.8 trillion USD) the current total global food consumption (9 trillion USD).

These externalities accrue from 7 trillion USD in environmental costs, 11 trillion USD in costs to human life and 1 trillion USD in economic costs.

This means that food is roughly a third cheaper than it would be if these externalities were included in market pricing.

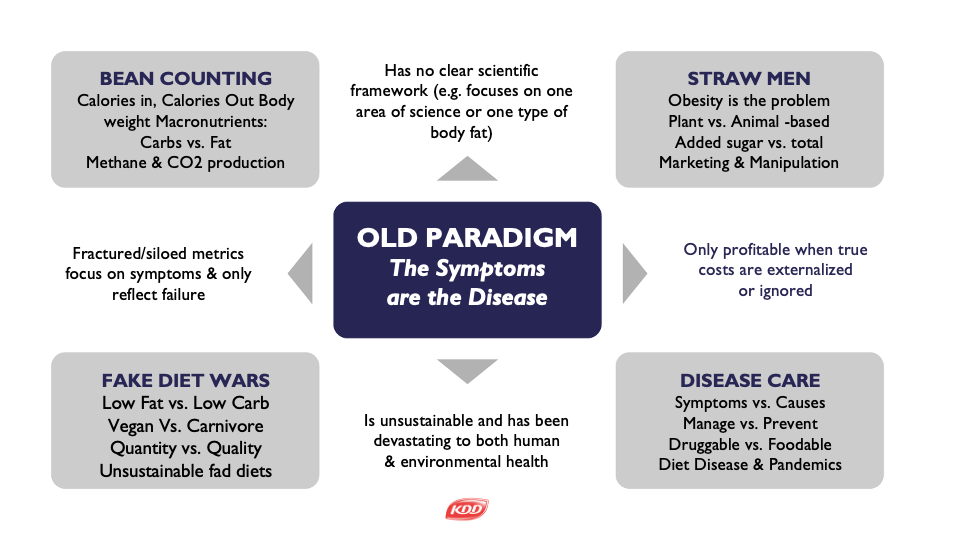

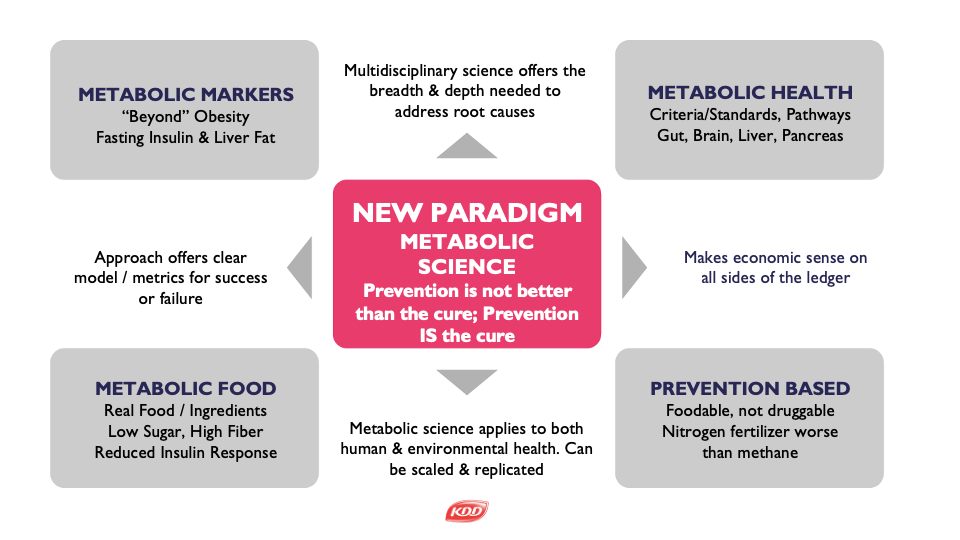

How food and beverage products are made depend entirely on what paradigm informs the process and the processing.

Two inconvenient truths:

1. There is no medicalized prevention for chronic metabolic disease. There’s just long-term treatment.

2. You can’t fix healthcare until you fix health. You can’t fix health until you fix diet. And, you can’t fix diet until you know what the hell is wrong.

A New Paradigm Places Metabolic Health as the North Star of Nutrition

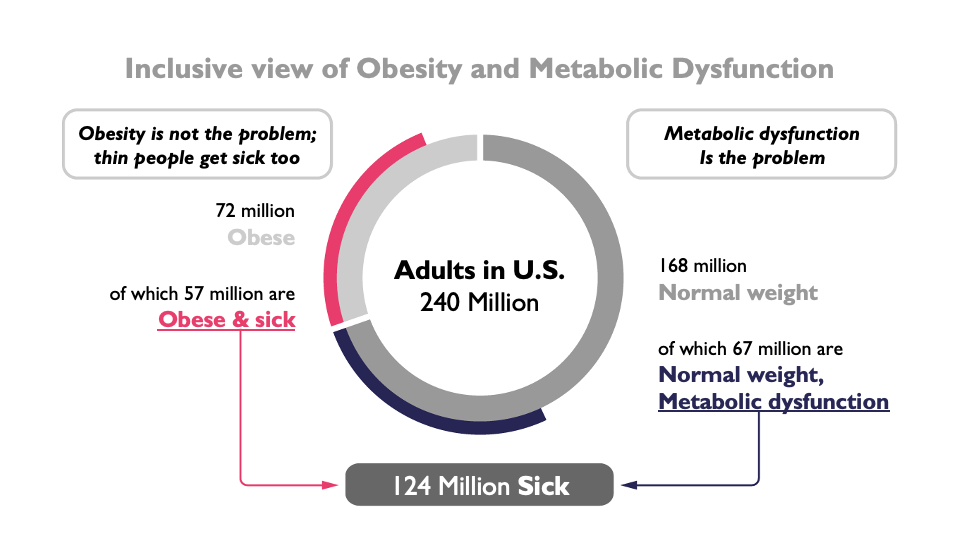

A new paradigm is emerging that looks at metabolic health at every size – it considers the total sum of humanity that is affected by metabolic diseases, and that the cause is far more complex than body weight or calories. In the U.S., despite the fact that 40% of adults are normal weight, only 12% are metabolically healthy[1]. Dr. Robert Lustig, world renowned pediatric neuroendocrinologist, author, and expert on metabolic disease[2], demonstrates this lucidly in the Venn diagram below. Twenty percent of obese people are metabolically healthy, while 40% of normal weight people are metabolically ill [3]. Metabolic disease affects children as they now get type 2 diabetes and fatty liver disease [4], and metabolic disease is considered to be a leading risk factor for mortality from the Covid-19 virus[5].

Obesity is not the problem

People don’t die of obesity. Obesity is a marker, not a cause – thin people suffer from metabolic disease too. All metabolic diseases are increasing globally, and this is where all the money goes (75% of all healthcare dollars). Here are the TOP TEN metabolic diseases:

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

- Lipid abnormalities

- Cardiovascular disease

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- Polycystic ovarian disease

- Osteoporosis

- Chronic renal failure

- Cancer

- Dementia

These diseases, when they cluster together are collectively termed “metabolic syndrome”, and occur in normal weight and even underweight people as well.

Fatty liver disease is the sentinel disease

Fatty liver disease, once a disease primarily associated with alcoholics, is now known as Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and is one of the fastest growing chronic diseases on earth[6]. Fatty liver is present in underweight, normal weight, and overweight people and is accelerated by ultra-processed, sugar-laden, fiber-poor foods and beverages. Research shows underweight patients have a higher risk for mild to moderate NAFLD compared to the matched controls with normal weight. In the U.S., 74% of food products sold have added sugar[7]: the human liver is being turned into foie gras (ironically, a liver disease sold as a culinary delicacy[8]).

Four out of ten adults in the U.S. now have NAFLD, and two out of ten children are affected by NAFLD. The mechanisms of NAFLD are complex and involve multiple pathways. Research shows that NAFLD is not only a liver disease, but also the precursor to the development of other chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.

Overnutrition and undernutrition overlap

A common denominator of both underweight and overweight populations is malnutrition[9] – nutritionally poor food that destroys both physical and mental health. The reason for this overlap is that the word “nutrition” is commonly confused with energy. Energy plays a minor role in nutrition. The consumables that truly determine health are protein and micronutrients, irrespective of energy. These are the nutrients in short supply in ultra-processed food.

In order to understand how the ultraprocessed food diet affects the Big Ten diseases cited, one must understand the difference between nutrient deficiency and excess. If we feed a healthy individual with the “right” amount of calories per day — say 2,500 to 3,000 — but provide only sugar as the food source (say 700 grams/day), that person will exhibit weight loss and not survive more than 2-3 weeks. In contrast, the same number of calories supplied as processed food rapidly devolves into massive weight gain with miserable and adverse health outcomes.

It’s more than enough calories in both cases; one caused weight loss, and the other weight gain — yet both put health at risk. Ultraprocessed food consumption crowds out real food in the diet, and also leads to micronutrient malnutrition. Nutrient deficiency diseases can bear striking resemblances to nutrient excess diseases.

For instance, consider the following set of nutritional diseases with too little body fat:

- Marasmus[10] (protein-calorie malnutrition) versus Kwashiorkor[11] (protein malnutrition). Kwashiorkor has fatty liver and metabolic syndrome, driven by insulin resistance.

- Lipodystrophy (a genetic defect of fat cell development). Lipodystrophy patients are thin, but they have fatty liver type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome, driven by insulin resistance.

Metabolic disease is akin to “First-World Kwashiorkor”

Kwashiorkor is a metabolic disease due to protein and micronutrient deficiency without calorie deficiency. These babies have huge bellies because their livers are filled with fat. What caused the fatty liver? Cassava flour — a high-carbohydrate, low protein, low-fiber food, is turned by the liver into fat, but then the liver cannot export it out, and the liver becomes fat-laden and insulin resistant. In other words, they have “Third-World Metabolic Syndrome”.

Similarly, people with metabolic syndrome are both energy overnourished and protein and micronutrient undernourished. They consume plenty of calories, and they get lots of protein in general, but they are deficient in the two rarest amino acids needed to fight metabolic disease, specifically tryptophan (needed to make serotonin) and methionine (needed to make glutathione, the liver antioxidant). They’re also deficient in micronutrients from eating grains that have been stripped of their germ (location of the vitamins, polyphenols, and minerals). They have “First-World Kwashiorkor”.

Metabolic disease is also “Acquired Lipodystrophy”

Lipodystrophy also explains the dissociation of obesity with metabolic syndrome. Because they don’t make fat cells, they are not obese; rather, any extra energy needs a place to be stored; it ends up as fat in the liver, which leads to all the diseases of metabolic syndrome.

Whether people get lipodystrophy has nothing to do with calories. Similarly, once obese people can’t store any more energy in their fat tissue, their fat cells stop working. They overflow their livers with fat and then they get metabolic syndrome as well.

The concept of “overnutrition” is a confusing choice of words because it assumes all of the food is of equal quality. But when the food is energy-rich and nutrient-poor, you can be both “stuffed and starved” at the same time. And this is what happens to people who consume ultra-processed foods[12] that are not only nutritionally poor, but also contain toxic calories (high amounts of added sugars, and processed carbohydrates that trigger a wide range of metabolic and mental health disorders[13]). The damaging effects of ultra-processed foods are catalyzed by the addition of a wide variety of food additives, many of which trigger or accelerate metabolic and immune system dysfunction[14].

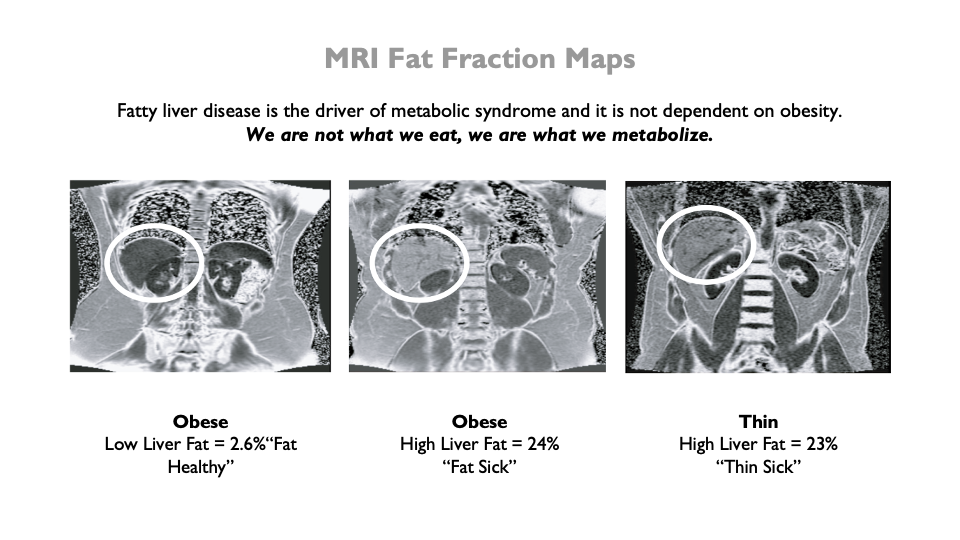

Focusing on body weight is an incomplete synthesis of the problem, and it has been tragically misleading. It is much more valuable to know fat, bone, and muscle masses, and especially what type of body fat is present, where the fat is accumulating, why it is there, and what causes it [15].” More simply put, there are three different drivers of metabolic syndrome: 1) obesity (subcutaneous fat), 2) stress (visceral fat), and 3) diet (liver fat). All can contribute to liver insulin resistance, which underpins metabolic syndrome, regardless of weight or BMI. But only the diet is amenable to societal intervention.

Tragically, at a time when metabolic disease has reached pandemic proportions, many of the authorities that are supposed to define what constitutes a healthy, sustainable diet have digressed into fractious, unproductive, polarized, and contentious debates over plant-based versus animal-based diets, macronutrient ratios, and calorie counting – (calories in, calories out)[16]. The “diet wars” frameworks have shown to be extremely ineffective strategies for addressing the actual problem, let alone fixing it.

Reframing the problem around metabolic health aligns with climate science (ecosystems are essentially metabolic systems functioning on a macro scale). Many choose to focus on the effects of changing temperatures and global warming on climate change and ignore the extensive evidence showing that the science of metabolism is a fundamental pillar of climate science and sustainability. The quality of inputs into both metabolic systems and ecosystems is of critical importance. Metabolism provides an essential scientific framework for integrating principles of physics, chemistry, and biology with the health of individual organisms and the ecology of populations, communities, and ecosystems[17]. The manner in which organisms metabolize materials and energy (what humans call food), is a critical component of sustainability.

It is now clear that we will not solve environmental problems by simply counting CO2 molecules in the atmosphere just like we will not solve metabolic disease by counting calories or pounds of body weight. Diet wars and political debates proffer overly-simplistic, reductionist, and unscientific views by quantifying food and health issues with siloed datasets rather than understanding the interrelated and complex scientific processes that are at the root of the problem.

Overloading biological systems with toxic materials foster cellular dysfunction, and disrupts metabolic pathways making organisms[18] and whole ecosystems sick[19]. We are not what eat. We are what we metabolize. Metabolism is a biochemical process that is highly complex and affects all the systems of the human body. This diagram reveals some of the complexity of metabolic syndrome signaling[20], and demonstrates that the liver is at the center of the cascade of events leading to metabolic syndrome.

Metabolic health and sustainability

Environmental compounds, for instance, endocrine disrupting chemicals, are increasingly implicated in the global decline in metabolic and ecosystem health[21]. When human metabolic systems are disrupted, it is analogous to the disruption of food chains in complex environmental systems (not coincidental since many of the same toxicants are at the root of the problem). When metabolic pathways are disrupted, the implications ripple throughout the entire human body, and toxicants can bioaccumulate through entire ecosystems[22].

In summary, metabolic health must be viewed in the context of the “Exposome[23]” — the total sum of environmental factors that drive health or disease[24]. Such a view provides a solid foundation for connecting human metabolic health with sustainability.

We must answer these questions:

- What can the industry do to provide food and beverages that address the global health crisis and improve, rather than erode, metabolic health by providing nutritious, safe, affordable, and accessible food?

- How can shifting to a model of sustainability that integrates metabolic health with ecosystem health improve understanding of the problem (and therefore the solutions), thereby meeting the demand for products that create net-positive impacts for health and the environment as a major growth driver for food companies?

- What transformations and integrations are needed in the food, health, and business systems to ensure metabolic health, and improve and sustain health, environments, and economies on local and global scales?

[1] Only 12 percent of American adults are metabolically healthy, Carolina study finds

[2] Toward a Unifying Hypothesis of Metabolic Syndrome, Pediatrics

[3] Dr. Robert Lustig, Infographics

[4] What is metabolic syndrome, and why are children getting it? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences

[5] Metabolic syndrome and COVID-19: An update on the associated comorbidities and proposed therapies

[6] Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease – A global public health perspective, Journal of Heptology

[7] Hidden in Plain Site: Added sugar is in 74% of packaged foods, Sugar Science, UCSF

[8] Scientists and Experts Statements on Force-Feeding for Foie Gras Production and Animal Welfare

[9] Malnutrition: Key facts, World Health Organization

[11] 75 years of Kwashiorkor in Africa, Malawi Medical Journal

[12] Ultra-processed foods, diet quality, and health using the NOVA classification system, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

[13] The toxic truth about sugar, Nature 2012

[14] Effects of Food Additives on Immune Cells As Contributors to Body Weight Gain and Immune-Mediated Metabolic Dysregulation, Frontiers in Immunology

[15] Why It May Be Counterproductive to Say ‘Overweight’, Atlantic Magazine

[16] US researchers seek to end carbs v fat ‘diet wars’. The Guardian

[17] Metabolic Theory of Ecology, Ecological Society of America

[18] Polluted Pathways: Mechanisms of Metabolic Disruption by Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals, Current Environmental Health Reports

[19] Anthropogenic pollutants: a threat to ecosystem sustainability?

[20] Metabolic Syndrome Signaling, Bio-Techne

[21] Endocrine disrupting chemicals: a new and emerging public health problem? Archives of Disease in Childhood

[22] Metabolism Disrupting Chemicals and Metabolic Disorders, Reproductive Toxicology

[23] The exposome concept: a challenge and a potential driver for environmental health research, European Respiratory Review

[24] The exposome and metabolic health, UCSF Aging, Metabolism and Emotion Center Symposium.

Diet interventions that seek to alter the ‘external’ setting or choice environment, tend to be more effective than those that target ‘internal’ motivations.

The food system must deliver metabolically supportive foods in order to achieve metabolically positive health outcomes.

Humanity needs to produce enough food, fiber and feed to meet the needs of nearly 10 billion people by 2050 on the same (and ideally less) working land area that now provides for roughly 8 billion. This requires boosting yields while minimizing unintended environmental impacts and increasing urban density.

Metabolic health and nutrition are essential to human health. Unhealthy foods are a major risk factor for nearly 75% of all global deaths. Food is Medicine is a thriving movement built upon the idea that healthy foods are vitally important for human well-being and for preventing and managing both communicable and non-communicable diseases.

Our world is poised for another transformation (or collapse) and we must embrace the opportunity to transform our food system so that it is focused on human and environmental health. In order to do this, we need to throw out our broken cost models and economic structures and invest in disrupting the paradigms that are disabling us while working closely with the leaders who are leaning into the positive transformation of our food system. Only through collaboration and innovation will we have the power to increase the overall health and well-being of people, communities, and environments around the world.

Source: Transforming the Global Food System for Human Health and Resilience

Read the full report (click on the image above to access)